On View: July 3-July 31, 2020

This Video Viewing Room presented Lawrence Weiner’s video Do You Believe in Water (1976) for one month, from July 3 through July 31, 2020. The remaining components of the page include archival images, ephemera, and excerpts from a recent conversation between Weiner and The Kitchen’s Executive Director and Chief Curator, Tim Griffin.

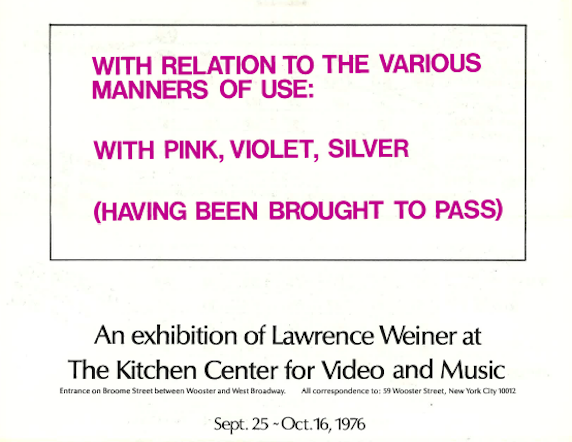

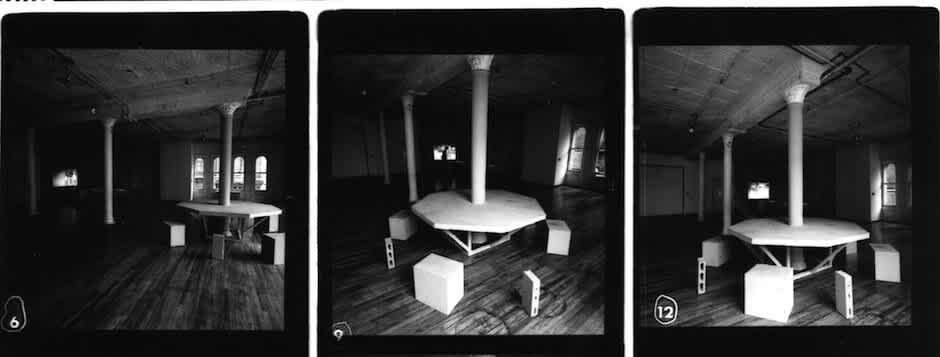

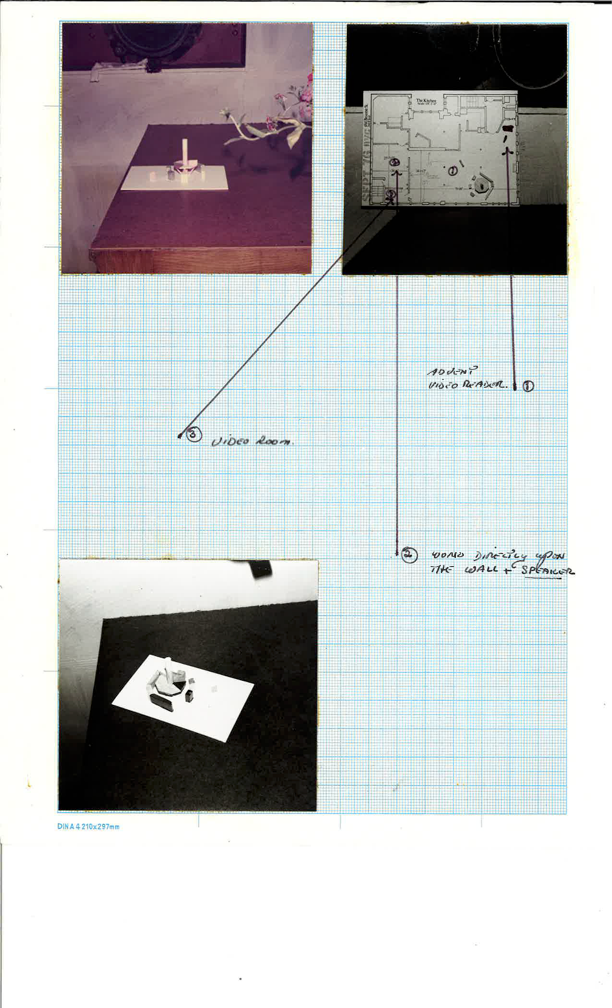

On April 28, 2020, artist Lawrence Weiner generously spoke with The Kitchen’s Executive Director and Chief Curator Tim Griffin about one of his earliest videos, Do You Believe in Water? (1976). Filmed in The Kitchen’s gallery at 59 Wooster Street and shown as part of Weiner’s 1976 exhibition in the same space, WITH RELATION TO THE VARIOUS MANNERS OF USE: WITH PINK, VIOLET, SILVER (HAVING BEEN BROUGHT TO PASS), the video raises questions that remain resonant—and expansive in implication—today. Excerpts from the conversation between Weiner and Griffin are included in this Video Viewing Room as part of an ongoing effort to present videos and ephemera from The Kitchen’s archive alongside new, contextualizing materials as we reconsider the organization’s history in anticipation of its 50th anniversary.

Tim Griffin [TG]: You were among the first artists to be working consistently at The Kitchen, making some pivotal early works like Do You Believe In Water? (1976). How did that piece come about?

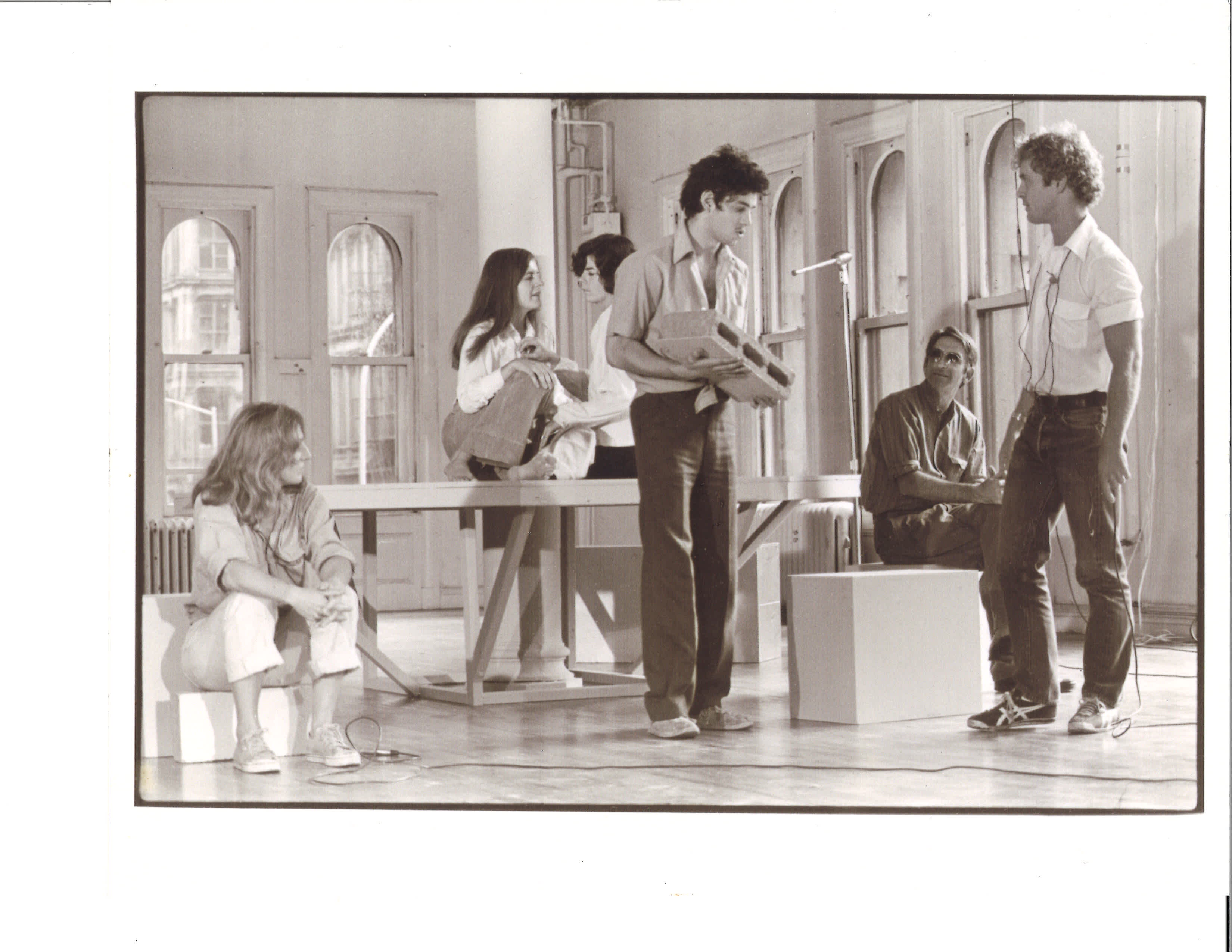

Lawrence Weiner [LW]: I was thinking at the time about what constituted disruption, in a sense. So I sought to put together a group of people, in a dance, who basically had lots in common but didn’t really like each other. Things came together to make the film at The Kitchen, and The Kitchen’s Video Director Carlota Schoolman said she would shoot it. And we just set about doing it.

I used to make a lot of tapes. We would just start off, and I’d go out with some friends and cast the cast. You go out and take a walk in the evening and talk to people and set it up, and then the next morning they all show up.

TG: Did people know that you had chosen them because they didn’t like each other?

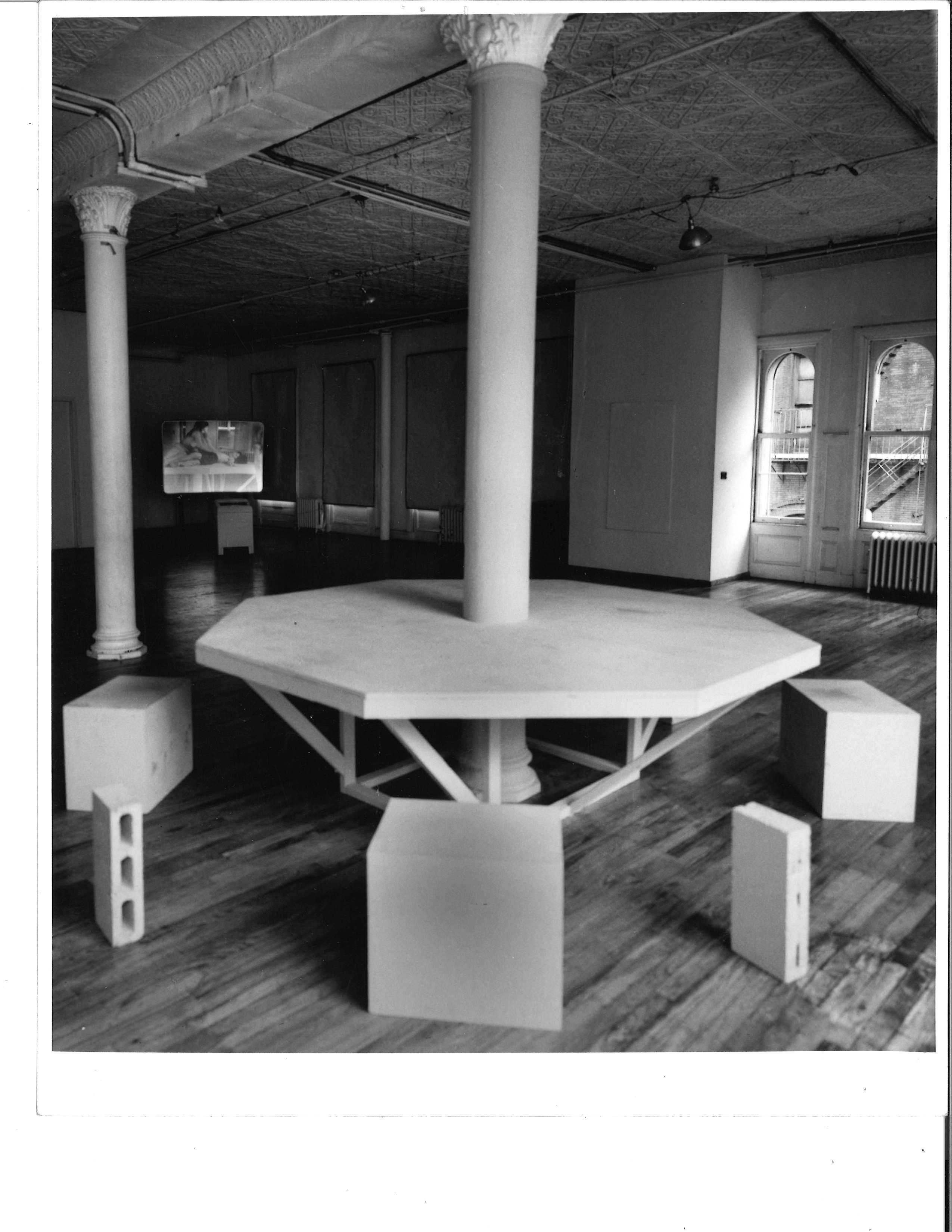

LW: They knew that they were standing for certain things. They made it obvious in the tape what they stood for. I brought together people who had developed personalities and developed roles within society, and asked them to see what it was like trying to occupy the space of a table [that was installed in The Kitchen’s space]. The table presented itself as a space to be occupied.

The nicest thing about making a tape is you don’t have to talk about it. It’s right on the face and the surface of the television. Whatever stress there was, you saw. I don’t make things that have to be discussed. I make things that you can look at, and that say what they say. And you can agree with it, or disagree with it.

TG: What did you ask people to do?

LW: Various motions and games. They were asked to do certain things, but not told how to do it. And they went through a series of motions. That’s it. Nobody chose their own activities. We used a cinder block as the moving integer. It was just heavy enough, and just so dangerous, that you had to be careful you didn’t drop it on your foot or something.

It was all about what the limits, and the extent of exploitation, were. And somehow or other, it didn’t have to be explained any longer. All the people involved in it knew what they were doing, and then they played it hard. What came about was the tape, and the tape was understandable from the beginning.

TG: So things were being kept elemental in many ways. But I’m hoping you can unpack that last thought just a bit for me.

LW: It wasn’t elemental. I don’t know where this having to make things specific comes from. It wasn’t elemental. It was a performance. Everything is theatrical. Everything in the world that you do for every person is theatrical.

TG: In the video, you pose the question, “Does it happen with relation to various objects of use?” What prompted the question, and how did you understand that question? I ask given how people are figured here, and as they are placed in relation and a kind of dissensus.

LW: I have no idea. I don’t remember. You see, the nice thing about doing a registered performance is you don’t have to remember what you thought. You have to remember why you ask them to do it, and then if they did it, you’d be saying “Thank you.” If they didn’t do it, you’d say, “Oh well, try again.”

TG: When you look at the video, do you feel like the people in it are doing what they were intended to do?

LW: They’re doing what I asked them to do, which pleases me very much. But I didn’t tell them what to do. I asked. And they engaged and showed off their skill. Because it is a performance. You’re not giving a reflection of yourself. But your personal feelings still come out in body language.

TG: How does that come out here?

LW: It was 1976. Most people were more than happy to go into a performance situation, where they could carry with them their own politics. And for each person involved, it was something. Steve Blutter was trying just to bring about his own sense within an older group of people. Suzy Harris was an old pro. Norman Fisher was basically a pro. And on and on. And Madeleine Burnside and Ann Sargent-Wooster were supposed to be grooming each other, but they decided to use the occasion to come out. Which everybody was more than happy to help them do, with some elegance.

I thought the tape was a great success because all the interpersonal relationships on the tape are obvious. There is no hidden under-meaning. If so-and-so was uncomfortable around something, they showed it. They did what they had said they were doing.

But remember, this was a time when people were making movies and there was a rule: you discussed everything before you started to shoot. Once you started to shoot, the red light went on. And that was it. If you hadn’t ascertained who you were and what you are in this movie—and, in this case, the tape’s point was that the exploitation of gesture is a cultural exploitation—that was it.

The main purpose of making the tape Do You Believe In Water? was to lay bare the creative aspect of the whole thing. And the creative aspect was what turned out later to have been something that interested me—that sensuality was one thing, and immediate viscerality was the other. And you have to deal between the sensual and the visceral. The sensual is long division and the visceral is short division.

TG: How was the video first shown?

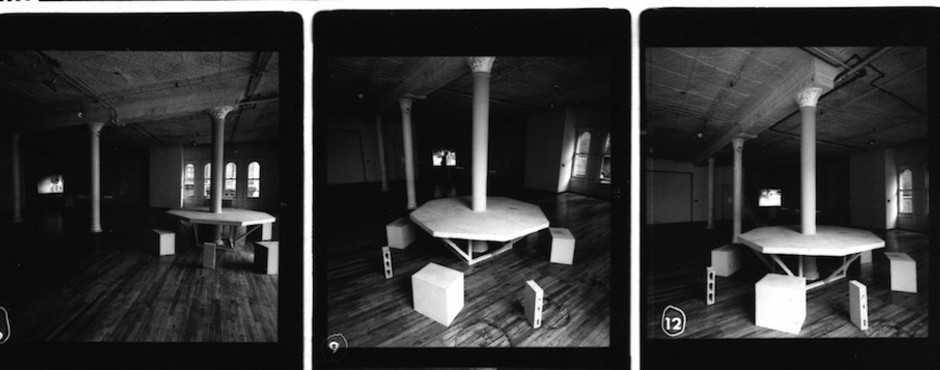

LW: It was shown in The Kitchen on one of those Trinitron video monitors—big, three-color ones—as part of my exhibition at The Kitchen [WITH RELATION TO THE VARIOUS MANNERS OF USE: WITH PINK, VIOLET, SILVER (HAVING BEEN BROUGHT TO PASS) ]. An integral part of it.

TG: What else was in the exhibition?

LW: The table, the human beings, and the music. It was a gesamt production. It was all together.

TG: You created one public in the video, but another would enter onto the very same stage in the space. How would you describe that?

LW: The Kitchen’s gallery was open with the public coming in and out, and there were naked people in the video. Nobody complained. Nobody. It was a long tape. We’re not talking about five minutes or three minutes—we’re talking about half an hour. People noticed it and they looked at it and we didn’t know what they thought when they walked away. Since it wasn’t sociology, it was performance.

In many ways, ’76 was a different time. It was really open, and The Kitchen was a very open place. You could edit video in The Kitchen. And all the people you worked with knew what you did. If they didn’t like it, they didn’t work with you. There was no reward other than the work itself. And that’s what Do You Believe In Water? is about. It’s about what you do when the only reward is being able to maintain your own time-space within a public space.

BIO

Lawrence Weiner was a central figure in the formation of conceptual art in the 1960s. He has been using language as the primary medium for his works since the late 1960s. Presented in capital letters, his structures consisting of language, or text fragments, often accompanied by graphic marks and lines, have been exhibited around the world and interpreted into numerous languages. He exhibited his work and participated in events frequently at The Kitchen during the 1970s.