Credits:

Keenan Saiz, Winter/Spring 2020 Curatorial Intern

July 13, 2020

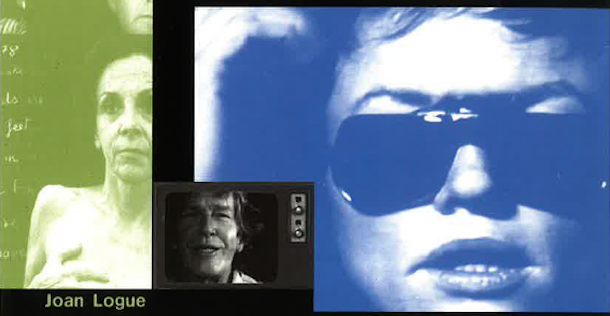

ARTISTS ARE SKILLED AT ADAPTING to ever-changing conditions in society and technology. During a time when artists are grappling with the circumstances created by COVID-19 and quickly developing new avenues to show their work beyond physical spaces, I was inspired to look more closely at the career of video artist Joan Logue and specifically at her series from the 1970s and 1980s that experimented with repositioning the visibility of contemporary art across new contexts, in part through several projects executed in partnership with The Kitchen. Across these decades, Logue established a career that combined portraiture, video art, and commercial advertising formats in order to bridge the gap between experimental art and popular culture, elevating artists toward new possibilities for public engagement that began to move outside of institutions. By examining the development of her work through her presentations at The Kitchen, I will show how Logue has utilized the format of video portraiture as a tool to position her subjects in new contexts that challenge fixed notions of visibility in society and that help artistic experimentation gain attention in mainstream media platforms and public spaces.

LIKE MANY ARTISTS INVOLVED WITH THE KITCHEN IN THE ’70s and ’80s, when the growing medium of video art was challenging the artistic standards of filmmaking, Logue embraced these new technological conditions as fertile ground for exploration. After being exposed to the Sony Portapak (an affordable, small-format camera) in the late 1960s, Logue began creating video portraits that depict her subjects in direct and revealing moments of vulnerability. Coming from a background in painting and photography, her filmmaking style exudes a sense of calculated composition that mirrors traditional portrait techniques while creating an environment that moves with subtle fluidity inside a tightly cropped frame. These visual elements create an arresting portrait of a person brought to life in an ephemeral moment—a moment that catches both subject and viewer in a reciprocal gaze across the television monitors or large projections that display this work.

As Logue sought to expand portraits outside of the static frame of photography and painting and into a medium that could better express the complexity of people’s presence, she recognized video portraits as what she called “the next step in portraiture.” Logue filmed her first video portraits in Liberia, and then continued making works that captured herself, family, friends, neighbors, working-class communities, activists, and artists (including many who were closely associated with The Kitchen) in cities across the United States and Europe. These early iterations of her video portraits range from ten to sixty minutes long and present a striking and diverse display of subjects simply gazing at the camera in an extended silence or occupying themselves in quiet mundane tasks. Through her visual treatments, Logue demonstrates the visceral and expressive qualities that connect all people, using her camera as a mediator between different individuals whose distinct worlds appear strikingly similar when seen via the contemplative act of sitting for a portrait. Over time, the artist redesigned her portraits for different purposes through presentations at The Kitchen, demonstrating their unique effects in various settings.

IN LOGUE’S FIRST PRESENTATION AT THE KITCHEN, More Portraits in 1981, she showed a selection of her early long-form video portraits in a group exhibition that also included works by Anne Doran, Mark Magill, and Mary Heilmann. In the show, the videos were displayed on television monitors embedded in the wall that resembled framed images. The slight motion present in each video portrait pulsated with a quiet irreverence to the static nature of a photograph. In a review of the show for the Village Voice, Ben Lifson commented on an “inherent drama” in each video portrait that creates “a temporary surrendering of character to situation,” implying that the mediation of the camera slowly erodes the psychological barrier between subject and viewer and illuminates deeper processes of thought behind each of Logue’s subjects that might otherwise be obscured in everyday life.

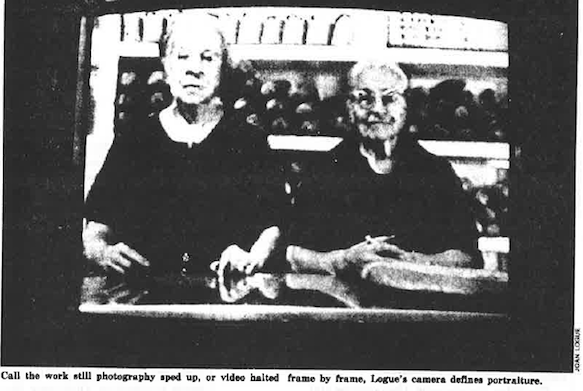

The possibility of making the hidden thoughts and emotions of her subjects visible beyond the gallery space enticed Logue to continue experimenting throughout the ’80s with new forms of installation and distribution for her videos. As a first step in bringing her work outside the walls of arts institutions, Logue partnered with The Kitchen for a second time in 1983 to present Video Portraits, an installation of videos highlighting Soho merchants in the storefront of the Spring Drug Co. on 184 Spring Street (only three blocks away from The Kitchen’s location at the time at 59 Wooster Street). Logue began creating the video portraits shown as part of her Neighborhood Series in 1978. By spotlighting footage of local working-class individuals in a Soho storefront, Logue created an installation that served to recognize her subjects’ long-standing presence in the community and to call attention to their changing circumstances amidst the neighborhood’s rapid gentrification. The artist’s insistence on visibility straddled the line between portraiture and documentation, elevating her subjects into a space of direct confrontation with a neighborhood that was becoming inhospitable to them.

Logue’s desire to bring people out from the shadows of society strengthened as she spent more time becoming acquainted with New York City’s artistic scene. After getting to know the effervescent and complex characters of the experimental art world by attending events like The Kitchen’s 1979 festival New Music, New York, Logue was inspired to focus her lens on artists, believing that they deserved attention within more mainstream contexts. This desire to create greater visibility for artists prompted her in 1979 to begin a series of innovative video portraits called the 30 Second Spots, funded by the National Endowment for the Arts and co-produced by The Kitchen. In this project, Logue applied the format, style, and condensed time frame of television commercials to present striking and intimate portraits of renowned figures in the experimental art scene. The motivating question for this series was, as Logue put it, why do “we know more about hamburgers and chewing gum” than we do about contemporary art? She attempted to change this imbalance by increasing the visibility of the video and performance artists she became acquainted with at The Kitchen through a pop culture format that challenged the divide between contemporary art and commercial advertising. Beginning with portraits Logue filmed in New York City, the series continued through commissions from CAPP Street Project in San Francisco and Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris (among other institutions) that gave Logue the opportunity to capture artists from around the world in thirty-second, single-channel portraits that also utilized state-of-the-art techniques of video art.

From 1979 to 1986, Logue created thirty-second artist commercials that featured many artists closely affiliated with The Kitchen such as Laurie Anderson, Nam June Paik, Charlemagne Palestine, Meredith Monk, Maryanne Amacher, Robert Ashley, and John Cage. Logue aimed to craft individual commercials that were faithful to each artist’s ethos but also had the potential to linger in the imagination like any popular advertisement. By deliberately using the structure of commercial advertisements to present portraits of working artists who often escape the attention of wider audiences, Logue made work that challenges ideas of what should be accessible and visible within a media landscape that prioritizes familiar commodities as the central subject of popular appeal. Logue’s representations of artists within the advertising format subvert traditional commercial aims, leaving a viewer wanting to know more about a creator rather than a product.

Logue originally produced the series of 30 Second Spots with the goal of broadcasting them on television in order to make contemporary artists household names. Her aim of wider distribution on mainstream media platforms created the challenge of negotiating how to present an artist with commanding visuals and sound while still remaining true to the minimalism of her earlier video portraits, in which she depicted people staring silently into the camera for extended periods of time. Each artist commercial is tailored to the artist’s creative presence and utilizes subtle tropes of sensory intrigue common to other, more traditional commercials, creating an aesthetic that borrows from popular advertising formats yet maintains a visual distinction from them through a deeper dimension of artistic experimentation. However since the artist commercials retain an aesthetic that is slightly different than mainstream advertisements, they thrived in the context of experimental arts television programming of the 1980s rather than as widely-circulated commercials: her works were aired on PBS’s series Alive From the Center: Artists’ Music Videos and Chicago public television’s Image Union in between other segments. Even though these programs were experimental, they still enabled her work to extend beyond the gallery and find a new agency in public broadcasting programs.

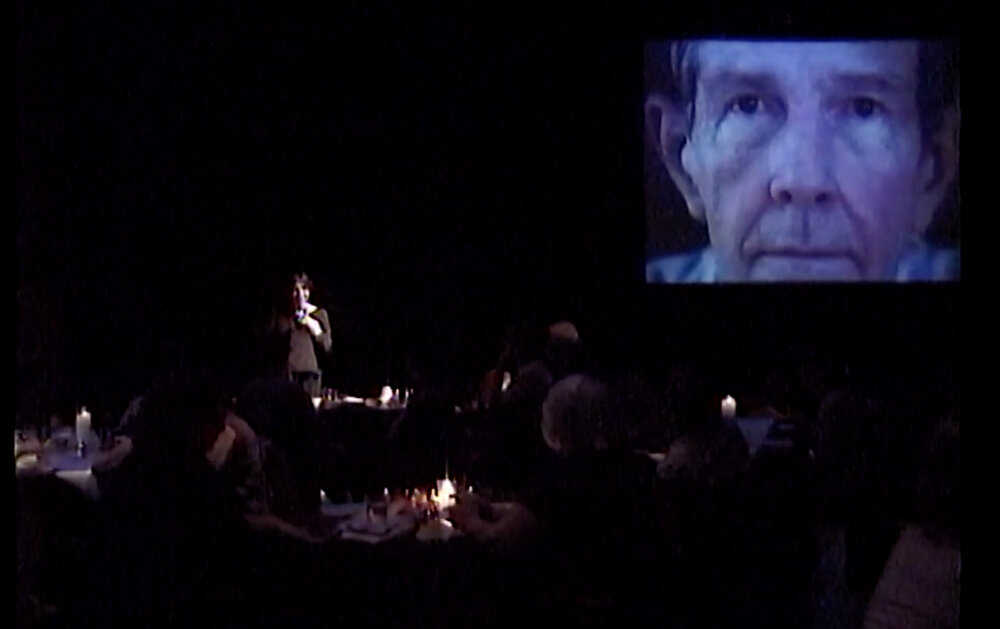

After the artist commercials were shown on broadcast television, they went on to be featured in numerous exhibits and festivals, becoming the work for which Logue is most recognized. On October 2 and 3, 1998 at The Kitchen, Logue had the opportunity to present her thirty-second artist commercials along with earlier video portraits of working-class communities and a concurrent video installation of a self-portrait during a TV Dinner event. This event was the first in a series that went on to run from 1998–2004; each TV Dinner featured video artists screening and discussing their work with a live audience over a three-course meal.

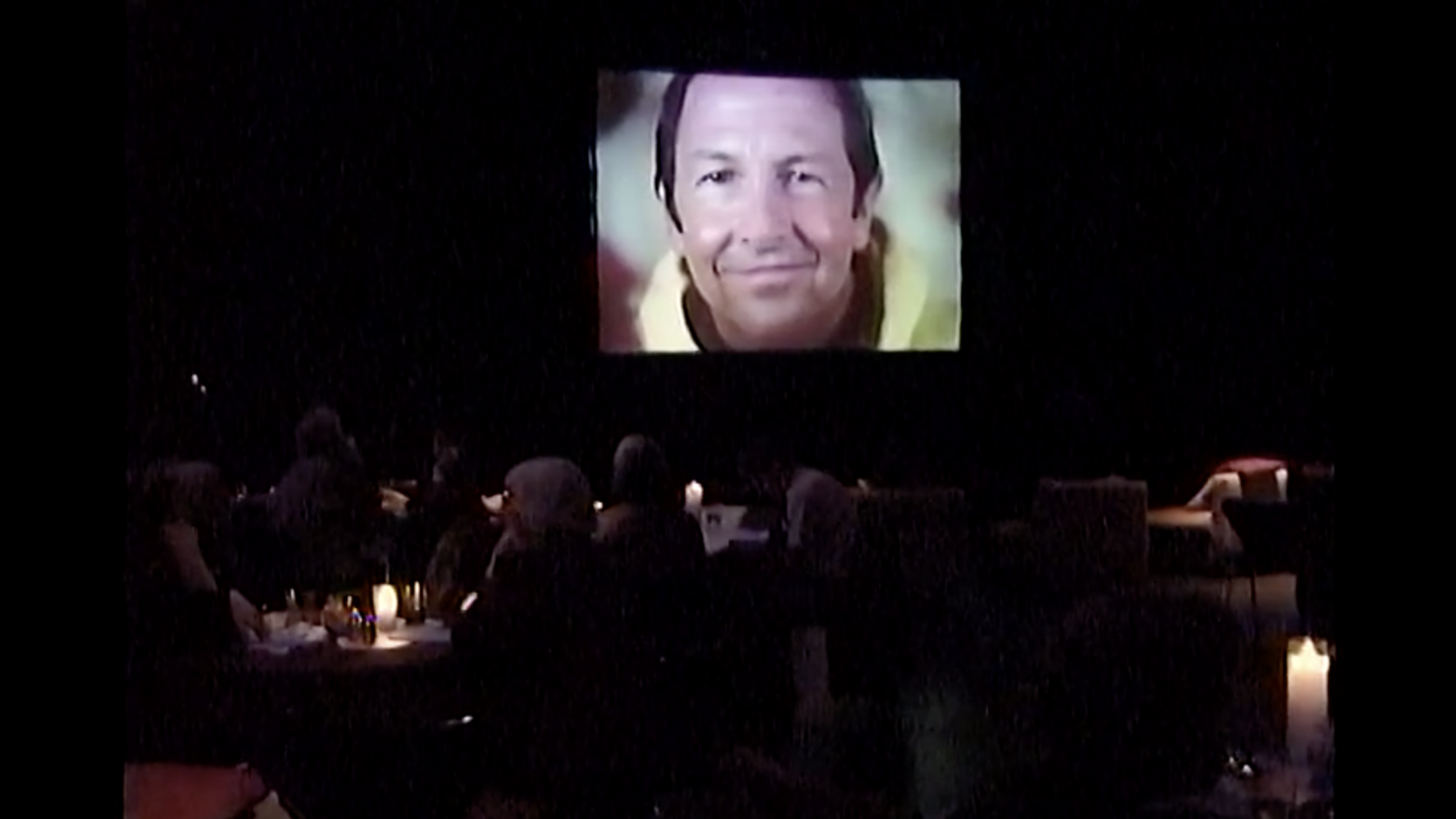

As audience members trickled in to Logue’s event to take their seats at candle-lit tables, a close-up of John Cage’s face was projected on a large screen that loomed amicably over The Kitchen’s first-floor theater space. After Logue gave an introduction, she screened for the audience a selection of the artist commercials shot in New York, Paris, and San Francisco, weaving together idiosyncratic moments between artists and their own movements, sounds, gestures, and personalities. Logue demonstrated attention to each artist’s distinct features through an intimate look into artistic process: musician Carlos Santos was shot from above as he pounded dissonant chords on the piano while belting out primal grunts and screams; French performance artist Orlan gazed into the camera while surrounded by blurry entrails of flowing fabric; Laurie Anderson used her head and teeth as percussion instruments in a close-up shot; and a tight focus on Steve Reich’s clapping hands illustrated his innate sense of rhythm. The TV Dinner event provided a space for the video portraits to breathe with new life in a formal theater setting as a culmination of the other contexts they once existed in.

OVER THE COURSE OF THESE THREE COLLABORATIONS WITH THE KITCHEN, Logue experimented with creating visibility for her wide-ranging subjects through the format of video portraiture across various contexts. From the gallery to storefronts to television broadcasts, Logue maintained an innovative approach to intervening in a traditionally defined setting in order to bring people from all walks of life into contact with new environments and audiences. The circulation of Logue’s video portraits—and especially her series 30 Second Spots—demonstrated that there are multiple spaces in which artistic experimentation can thrive and gain new recognition.