October 11, 2024

In celebration of its 50+ year Archive and the contemporary programs pushing the boundaries of artistic practices, The Kitchen is pleased to announce a new series of conversations with artists, past and present staff, and members of The Kitchen’s vast ecosystem. These conversations are anchored through The Kitchen’s original archival posters, which are available for purchase on The Kitchen's store, and serve as material histories and ephemera from The Kitchen’s programming.

In this conversation, Robyn Farrell, Senior Curator at The Kitchen, and Curator of The Kitchen in Focus at 47 Canal which runs through October 26, 2024 talks with Gilberto Rosa-Duran, Communications Manager, about the current exhibitions and the history of dance programming at The Kitchen

Gilberto Rosa-Duran: Let's go ahead and get started with the exhibition that's up right now, The Kitchen Focus at 47 Canal. Can you talk to us a little bit about that exhibition and particularly why it was important to showcase the history of dance programming at The Kitchen?

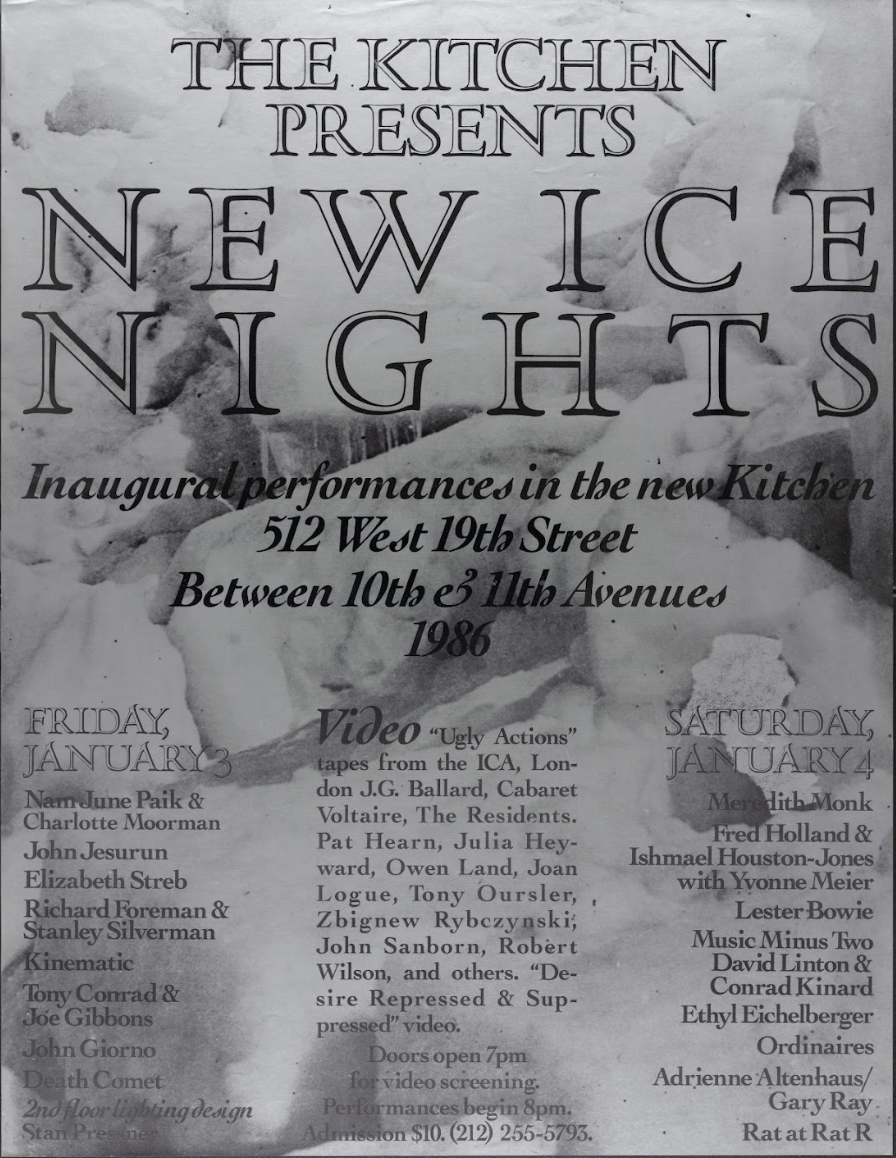

Robyn Farrell: Thank you. Yes. The idea for The Kitchen in Focus at 47 Canal was really born out of conversations with Oliver Newton, who is of course a co-founder of the 47 Canal gallery and a member of our board. 47 Canal is the new space for the gallery which opened this summer, and was also the Wooster Loft—the home that The Kitchen occupied between 1974 and 1985. So the exhibition came out of an interest in these shared histories, but also served as a moment to bring forth that history in a contemporary context.

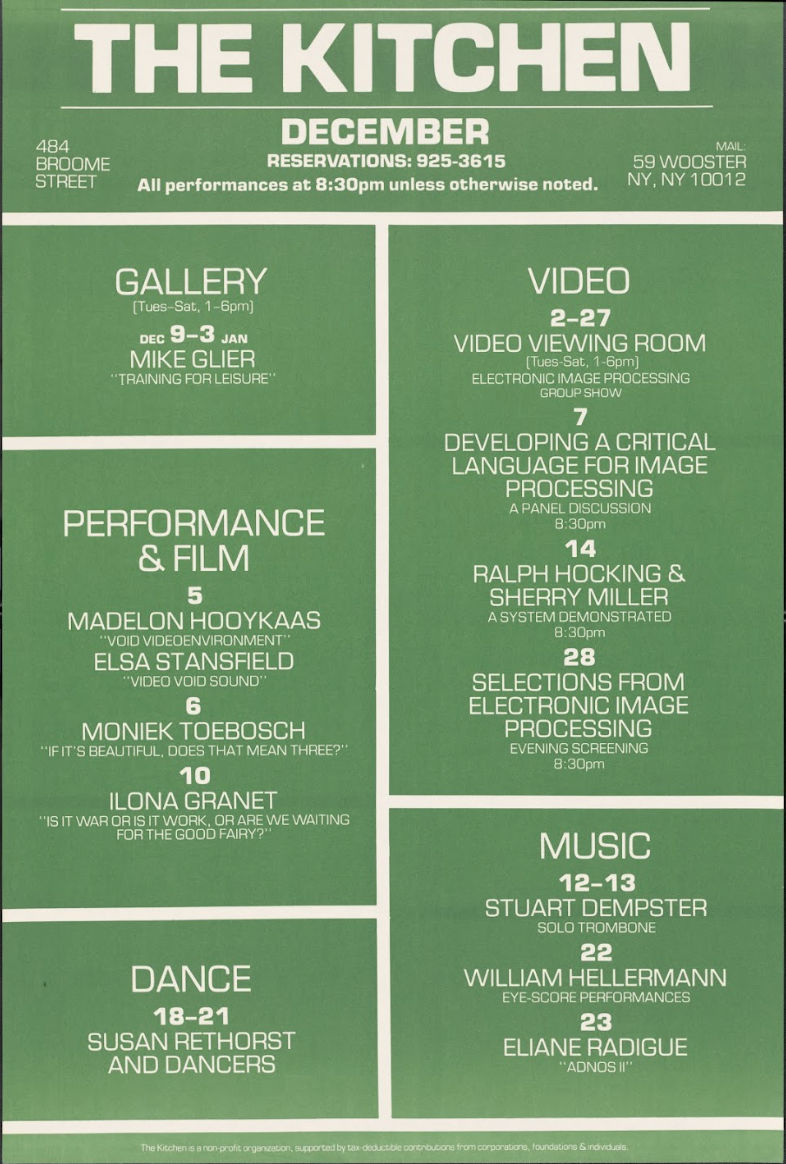

We agreed that a micro exhibition which looked at a particular artist or period of time in The Kitchen's history would be an exciting collaboration. I thought about what that could be. I dove into the Archive over the summer and was guided by an interest to highlight artists or works that were rarely seen or shown before, and ongoing dialogue with our Archivist, Alex Waterman. I wanted to focus on female-led work that took place in the late seventies and early eighties–revisiting well-known collaborations and bringing attention to those that may not have had visibility outside the New York performance community at the time. I initially was looking at doing a group presentation of three different female choreographers and dancers–Elizabeth Streb, Susan Rethorst, and Sheryl Sutton. And then of course, as what often happens with deep research, I fell down this rabbit hole, reviewing our “Dancing in the Kitchen” series which was established in 1978, and discovered Andy de Groat’s Gravy (1981)which included an accompaniment with Julius Eastman. This exciting collaboration, coupled with the dating of Sheryl Sutton’s performance Paces (1977) that predated the “Dancing in the Kitchen” program informed the 47 Canal two-part exhibition structure: one that would focus on Sheryl Sutton's, rarely seen, but very early and important work, archival materials, and Robert Wilson's television work, and three works by Elizabeth Streb, Susan Rethorst and Andy de Groat.

GRD: You touched on Andy de Groat's collaboration with Julius Eastman, which of course you mentioned in your talk at the gallery and was shown as part of the accompanying materials on de Groat’s work. Can you talk to us a little bit about that collaboration? How did you encounter that when looking through the archive? What was your initial response to it?

RF: I was looking at “Dancing in the Kitchen” histories from the late 70s and early 80s and Andy de Groat came up more than a few times. The Kitchen’s role as a space to create, present, and experience interdisciplinary work–an evergreen pillar of our program–is something I wanted to emphasize in his exhibition at 47 Canal. It's what I'm thinking about as I organize programs for our temporary space at Westbeth Artists’s Housing. This idea of seeking out collaborations that paved the way for interconnective work was really important to me and I was thrilled to include this particular collaboration between de Groat and Eastman. The material from our Archive, such as the fictional letter he wrote to Joan of Arc on and notated scores on program notes, was a distinctly new set of terms to consider this creative partnership.

So I thought here we have multiple entry points to the artist's hand. None of them are actually a direct connection, of course, because the program was reproduced from an original handwritten letter. So that's a reproductive media in and of itself. And then of course, the soundtrack, the music that you hear at the time is a recording, was indeed composed and conducted by Eastman, but as the story goes, Eastman handed a tape of a recording of the music to the organizers before the performance. So Eastman’s enigmatic spirit is captured here in the exhibition. I love this kind of circuitous way that he is involved in this particular collaboration with de Groat because it seems as though it's sort of like art imitating life there as well.

GRD: I am always really shocked by the folks that are connected in ways that can sometimes seem really siloed in the Archive. And I think it's exhibitions like these that revisit history and these iconic figures to show us how people really were in conversation with each other. And of course, The Kitchen is full of moments like that where folks are connected in really kind of beautiful ways.

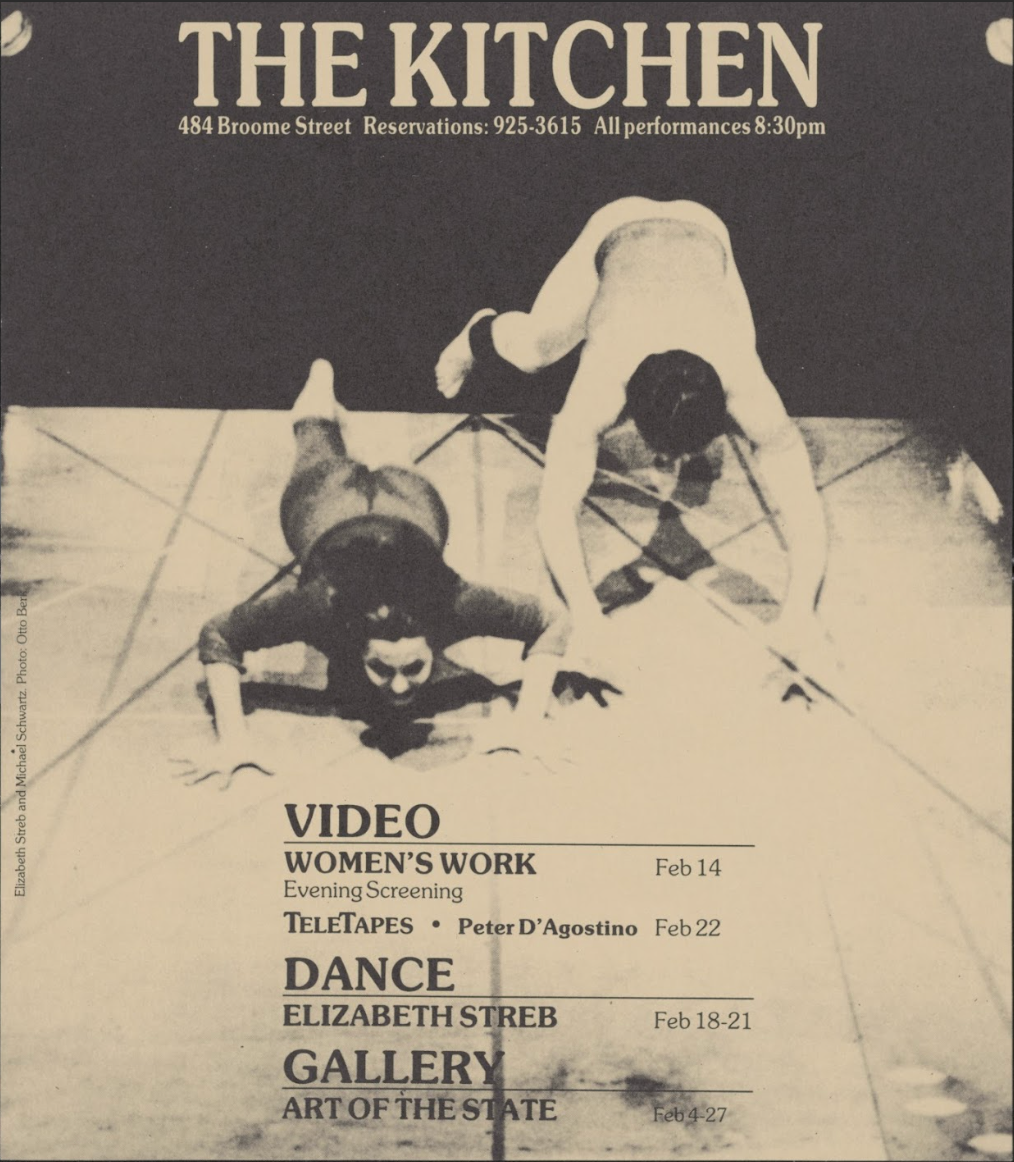

Moving on to Elizabeth Streb, she performed a few times throughout The Kitchen’s history. Talk to us about Streb’s work. What insights do you have into her multi-year collaboration with The Kitchen?

RF: I was working within this framework of the early years of “Dancing in the Kitchen,” at the Wooster Loft, so that informed my search and the selected performances. There’s a breadth of work and production by Streb at The Kitchen and throughout New York City in this period. The notion of physicality, of struggle, defying the boundaries of gravity and the body, are outstanding notes across her practice but carry particular resonance with her 1982 work Ringside/Fall Line, featured in the exhibition. As is the case in much of her work, Streb focuses on the tension and endurance of one's body moving through space; whether suspended, falling, or incorporating props, body work is an important touchpoint in both her solo and collaborative in this 1982 performance.

Streb’s work on the incline structure she calls “the hill” and its rope attachment in Ringside/Falline is a stunning example of this innovative work. I liked the juxtaposition between her and Michael Schwartz’s collaboration, seeing what two bodies–together and apart–can do, with Streb performing by herself, sliding and swishing across the surface.

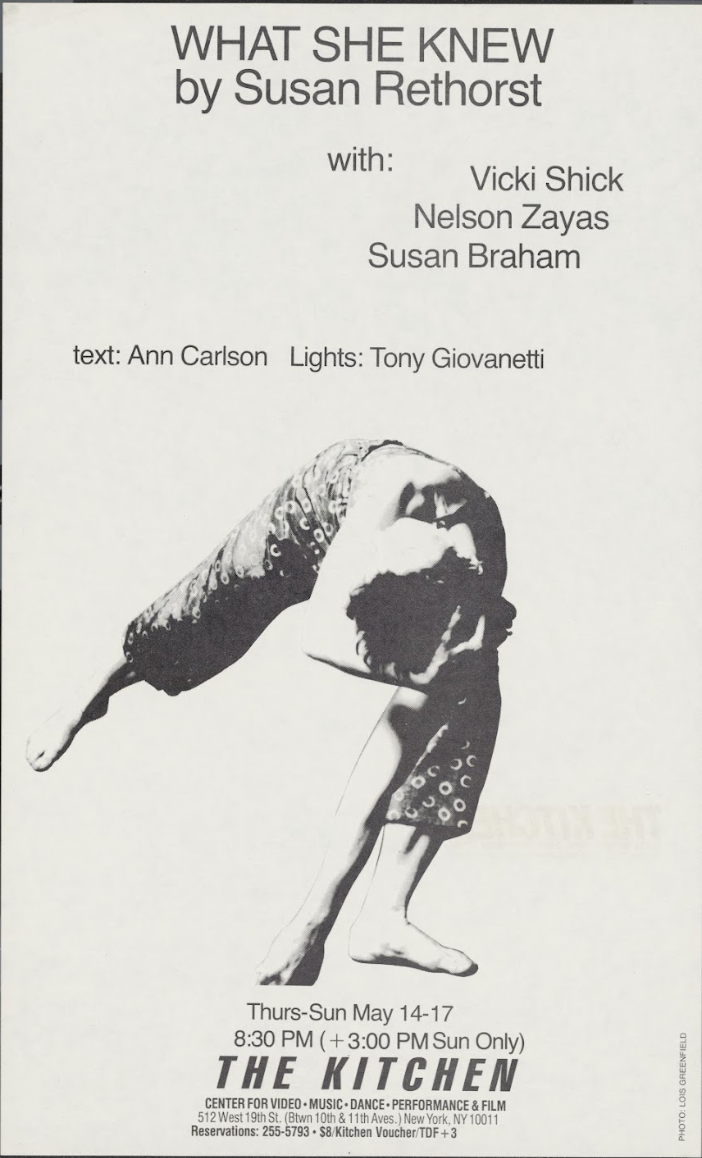

GRD: Susan Rethorst’s 1980 work, The Life of Wasp was also included in the show. In what ways is this show also in conversation with de Groat and Strep?

RF: The Life of Wasp is a sixteen-dancer performance that pushes the traditional modes of ensemble and soloist choreography. Minimalist aesthetics and organizational structures are at present in the piece such as repetition, deliberate movements, simplified gestures, and subdued costumes. Playing on the title of Doris Humphrey’s The Life of the Bee (1929) and on the socioeconomic label “W.A.S.P.", Rethorst simultaneously nods to dance history and comments on commerce and community. I think that Rethorst imbued a bit more of sociopolitical commentary than the other two works, which I thought was really interesting, while mining, of course, the same kind of physical aspects that are inherent to dance and choreography and performance.

GRD: I think that is a really good segue into talking about part two of The Kitchen in Focus and Sheryl Sutton's work. What drew you to her work and why did you feel like she needed her own moment in this exhibition?

RF: There's so many reasons. I was familiar with Sheryl Sutton, actually more through her collaborations with the theatrical filmmaking pioneer Robert Wilson. That was my entry point of knowing about her and her work. Alex Waterman had mentioned that The Kitchen actually had a digitized recording of Paces, this a solo performance that she presented at the Kitchen 1977, in our archive and I was immediately interested in building a presentation around this work and the conversation across media within 47 Canal space. The other video on view, Deafman Glance (1982), is a work Robert Wilson made for television broadcast in 1981, excerpted from his a five hour opera of the same name. Now this work has been distributed around the world in both televisual and video form, but one of its earliest instances of transmission was at The Kitchen in 1982 as part of our Video Viewing Room series.

So this iteration of The Kitchen in Focus brings together interconnected history with performance, television, video, and collaboration, and all at the same time, while bringing much needed attention and visibility to Sheryl Sutton and her work. She's a figure that is acclaimed and well-known within dance and theatrical circles, but has not received the kind of recognition or attention for her contributions to the field and her role in so many pioneering works during that period of time, and today.

GRD: I'm sure we'll hear more about this when we listen to Sutton speak during the closing program of the exhibition at 47 Canal, but how did her and Robert Wilson even meet? What was the context of their initial collaboration?

RF: Robert Wilson and Sheryl Sutton first worked together during the development (with members of the Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds) of Deafman Glance during a residency at the University of Iowa in 1970. Einstein on the Beach, which was a seminal work from 1976, and Wilson’s first collaboration with composer Philip Glass. Sutton and Robert were in conversation together at the performance and art center Watermill center a few years ago, where he’s the Artistic Director, and that's available online to watch. I’m looking forward to hearing more about Sheryl’s work with Wilson, the downtown New York performance scene, and abroad during her dialogue with Elliot Reed at 47 Canal on October 24.

GRD: The work that you're doing is just scratching the surface, I think it'll be good for folks to do their own research as well into the life and work of Sheryl Sutton.

RF: Absolutely. There is a substantial amount of material on Robert Wilson’s career, but I think it's important to note that Sheryl herself is an important contributor to the theatrical avant-garde and one of the only women of color in that creative space. Her work in Wilson’s–which is on view at 47 Canal–underscores the dynamics of race and her ability as a performer to embody this deliberately slow and intentional style experimental movement, at the same time. while representing . I appreciate that Wilson gave her this spotlight and opportunity to star in this kind of televisual work. In the 1980s, you didn't see a lot of people of color in an avant-garde production. That was also something that was quite wonderful about their relationship, that it was sustained over time: he really was able to situate her in spaces that not only highlighted her work, but also increased visibility for people of color to be seen both on stage and and in this case on television. Tina Post devotes significant attention to Sheryl in her 2022 book, Deadpan: The Aesthetics of Black Inexpressions and Hilton Als’s “Lives of the Performers” is loosely based on her life and work and explores the significance of her presence and contributions to the field.

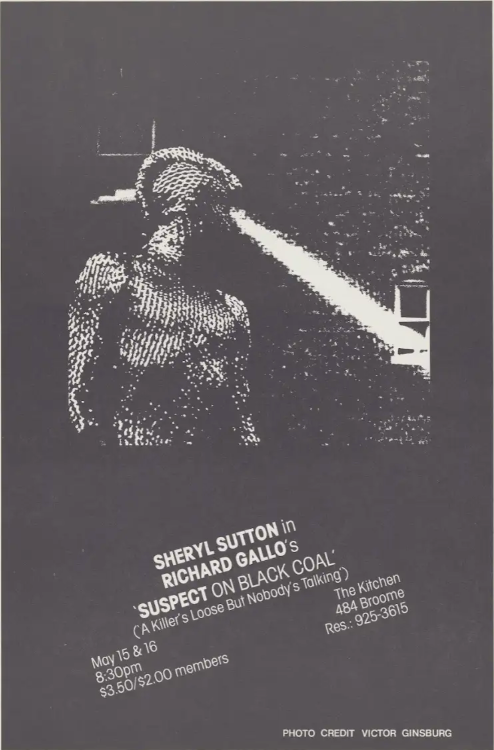

GRD: Shifting gears to the collaboration between Sheryl Sutton and Richard Gallo, that's also a part of the exhibition, A Killer's Loose But Nobody's Talking (1980). Talk to us a little bit about that performance. What kind of show was that?

RF: Unfortunately, the performance was not recorded, so I’ve never seen it. Our records actually suggested differently, that filmmakers Alan and Susan Raymond were going to film the work and it would be shown on public television, but a recent conversation with Alan Raymond confirmed they did not end up filming the work. So this is kind of a classic case of curating and researching from an archive, which sometimes presents more questions than answers. I tried to provide the most information–both visual and textual–that could bring someone into space and give them a sense of the atmosphere and environment for this work. Thankfully, Richard Gallo was quite prolific in both his writing and material-making for this particular performance. It was an excerpt from Suspect on Black Hole, which was a production that Gallo produced and was shown in Munich in the fall of 1980, and starred Sheryl Sutton. Gallo talked about the performance as a mechanical vision of the brain and the archival images included in the exhibition demonstrate this manifestation of a subconscious mind. They were kindly lent to us courtesy of Robert Wilson's Art Foundation.

The way in which Gallo describes it is: “A Killers Loose But Nobody’s Talking…utilizes the so-called ‘mechanical vision’ of the brain” images recorded by the subconscious mind, unrecognized by the conscious mind. It is so when the person is faint and the eyes are open / when the brain reels with dizziness and all things seem to swim into indistinctness of meaning / mechanical vision is present in certain forms of dementia / in magnified visions of delirium / example flying pigs in a triangular formation / this visual study of the subconsciousness is also linked to the phenomenon one experiences just before falling into deep sleep / known as REM / rapid eye movements / during which time hundreds of memory flashes are scanned by the mind / a conscious dream comes as a result of this intense memory search process / this romantic drama of ordinary everyday life / too perfect to be lived as seen through Gallo’s vision of growth and devolution passes through states of experience which surpass the most amazing flights of the intellect while the ordinary sense of conception is wrapped in oblivion.”

This is some of the language that is included both within the press release for The Kitchen's performance, but also in the separate handout that he produced on the occasion of the performance. So we have images that show the set and stage with Sutton in various modes of costume such as suspended from her feet with head pointing down towards the stage or swinging across the loft. In another view, her hair is dyed what looks like white or gray, maybe blonde, and she is in a dark costume. She's kind-of hoisted with her belly facing the floor. So this was quite an acrobatic feat. And other images reveal, like I said, these suspended pig carcasses, Gallo and a child in costume, as well as a woman that he invited off the street to be a part of the performance. I mean, it's a no holds bar performance that unfortunately none of us will know beyond this documentation. But we have this source material that reminisces and paints the picture for us so that we can attempt to get a sense of what it was like to see the performance in May of 1980 at The Kitchen.

GRD: I love the picture you just patined for us of that performance, and obviously working at a performance arts organization, we deal with questions of ephemerality all the time, so it's only natural that we would fall in love with something that we are unable to see or reproduce. Richard Gallo's description of the performance is just so poetic. It’s easy to be drawn into this meta state he’s created for the audience.

One last question: we just had our culminating performances as part of Dance and Process this past weekend and are simultaneously revisiting dance programming in the late seventies and early eighties in your exhibition. What are some of the themes you see arise in dance programming throughout the past 30 years?

RF: There's a lot of overlapping threads, I think across the work that we have presented at 47 Canal and all the way up to what we all were privileged to see at Westbeth recently—the culminating performances of Dance and Process with Rena Anakwe, ms. z tye, and Ogemdi Ude. The first word that comes to mind is newness. This is very simple, but it's also very accurate because I think that in each instance from 40 or 50 years ago or when I was there for the DAP performances last week, there's like an overarching sense of curiosity and wonder for varying perspectives towards performance, movement, and engagement. It is like an exhilarating openness, and the energy you feel is undeniable. And I think that that is something that comes through with these video recordings. When I asked Sheryl Sutton about her experiences at The Kitchen, she said it was both frightening and also very exciting. I think that that must be something that many people feel when given the support and space to perform without inhibition. In "Dancing in the Kitchen" series, and I think parts of this remain today, is that there's this opportunity to experiment and present something that a particular artist has not done before. That's because The Kitchen gives this platform and provides this place to explore, to create and to fail and just to exist. And that’s what is so remarkable and outstanding about our history. These fundamental grounding points of our mission are steeped in each one of the works we’ve presented at 47 Canal but they are ever present in any work presented during The Kitchen’s five-decade history. Collaboration, coordination, and community–all simultaneously at work at The Kitchen. These are all radical works about the body in space and time.