Credits:

Olivia Guerriero, Fall 2019 Curatorial Intern

December 9, 2019

This month, choreographer and performance artist Lauren Bakst performs after summer, or not in the kitchen (the bed, the bathroom, the dance floor and other spaces) as the culmination of her residency through The Kitchen at Queenslab. The phrase in the piece’s title—“not in the kitchen”—is a play on the fact that she is in residence outside of The Kitchen’s institutional building. It also recalls the title of The Kitchen’s first series of dance programming, Dancing in the Kitchen. Based on this echo in naming, I was inspired to look through the archives at The Kitchen’s dance history.

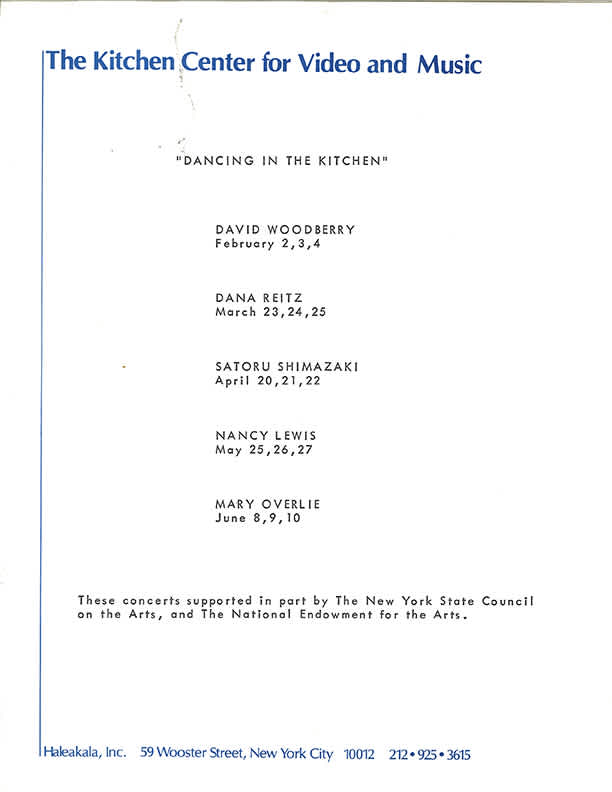

For the first six years after The Kitchen’s founding in 1971, dance performances were commissioned one at a time, without the structure of a formal dance series within each programming season. In 1977, however, The Kitchen received a grant to produce six dance concerts, allowing for the creation of The Kitchen’s first named series of dance programming: Dancing in the Kitchen. Staff member Eric Bogosian assumed the responsibilities of Dance Curator and, in the spring of 1978, organized the first performances in the series, which featured works by David Woodberry, Dana Reitz, Satoru Shimazaki, Nancy Lewis, and Mary Overlie.

After receiving criticism in publications such as The Village Voice for choosing to spotlight choreographers whose careers were already well-established, Bogosian committed to seeking out new names in dance to include in programming for the following seasons. He began to “audit” dancers around the city, going to any performance at which his presence was requested. He saw around 200 concerts in a year in order to find artists for Dancing in the Kitchen. In order to ensure that all artists had equal chances of presenting at The Kitchen, Bogosian’s auditing process applied to all artists, regardless of status or experience. In an oral history for The Kitchen in 2009, Bogosian described his response to artists who came to him directly asking for a gig: “We’re not a place that just books people…Do you come to see things here? Is this a place you want to be a part of? Because this is a dialogue.” He not only was looking for work that was fresh and interesting, but also was aiming to connect with artists who could be (or already were) an active part of The Kitchen’s community. Even through the auditing process, Bogosian was supporting the city’s dancers, often going to loft performances with less than ten people in the audience.

Once established, the Dancing in the Kitchen series ran throughout each programming year, typically hosting one choreographer per month to perform an evening-length work in a three-to-four night run. One of the series' requirements was that all works had to be a world premiere, which meant The Kitchen was not only producing never-before-seen performances, but also supporting the development of artists’ careers rather than simply supporting individual dance pieces. Sometimes Dancing in the Kitchen included dance festivals, during which numerous choreographers presented shorter works as part of a showcase. This format allowed The Kitchen to curate a theme for the evening and bring artists into conversation with each other, helping to foster a sense of community between dancers. In a 2002 article for Dance Chronicle discussing the cultural importance of Dancing in the Kitchen and The Kitchen’s dance opportunities for the New York performance community, art critic Sally Banes notes, “The Kitchen staff consciously worked, not only to provide services for individual artists, but also, especially for the younger choreographers, to function as a service and networking center for an emergent professional community of artists.”

As the Dancing in the Kitchen series continued, The Kitchen maintained this commitment, writing in a grant proposal for the fall 1984–spring 85 season, “the main programmatic emphasis [of Dancing in the Kitchen] is upon the work of emerging artists who are building upon the previous generation’s investigations and making discoveries of their own.” Not only were all of the performances comprised of new works, but also many of the dancers themselves were a part of the new generation of post-modern and experimental dance. Some had been taught by the great names in modern dance, while others were creating their own pathways in dance forms. For many of these artists, the work that they created for Dancing in the Kitchen has gone on to play a prominent role in their oeuvre, and their relationships with The Kitchen have remained strong over the decades as well.

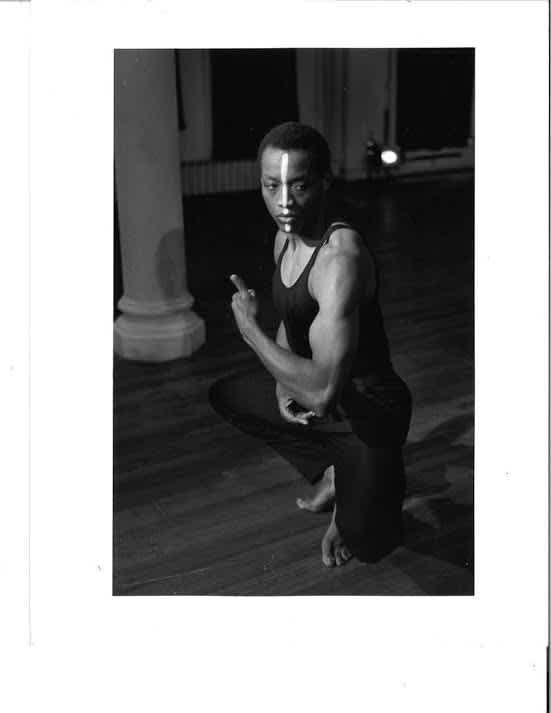

Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane were among the first artists to present work in the context of Dancing in the Kitchen. The pair had been collaborating with one another for several years by the time they debuted Monkey Run Road at The Kitchen in March of 1979, as part of the series. The piece later became part of a trio of duets, which was ultimately incorporated into the repertoire of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company. In 1982, Jones showed other works as a part of Dancing in the Kitchen, in a program titled Four Dances (also known as Four Duets). In the first part of the program, Jones danced a solo while, behind him, Keith Haring painted an original scene on the wall; the sounds of Haring’s breathing and his paint bucket were the only audible accompaniments to Jones’s movement. In his work today, Jones still collaborates closely with artists from other disciplines, often incorporating text, visual art, and digital media to explore forms of multidisciplinary storytelling.

Elizabeth Streb also performed at The Kitchen early in her career. Her first appearance was in September of 1979, as a dancer in Molissa Fenley’s performance for Dancing in the Kitchen, titled Mix. Streb returned in 1982 to perform some of her first choreography, showing two pieces called Fall Line and Ringside as part of Dancing in the Kitchen. These works explored gravity, physics, and the limitations of the human body under specific conditions. This exploration has become the focus of Streb’s ongoing career and company, and, to this day, she continues to test the boundaries of what the body can endure and what kinds of spectacle can be created by danger. Upon forming her company, she first called it Ringside, after her 1982 performance piece. She later changed the name to Streb Extreme Action.

In addition to Jones, Zane, Fenley, and Streb, other emerging artists who performed in Dancing in the Kitchen included Yoshiko Chuma, Pooh Kaye, Susan Rethorst, Ton Simons, and Karole Armitage.

In 1990, The Kitchen’s Dance Curator at the time, Steve Gross, restructured Dancing in the Kitchen, re-naming it Working in the Kitchen. As articulated in a press release for Working in the Kitchen’s first season in May 1990, the changes to the original structure hoped to respond “to two of the most pressing current concerns in the artistic community: the availability of affordable space in which to work; and the fracturing of the artistic community of New York.” Within the new program framework, Gross brought together eight emerging choreographers each season to workshop new pieces together over the course of several months. This format allowed the dancers to give each other feedback and assistance, while also receiving increased support from The Kitchen’s curatorial and technical staff throughout the creation process.

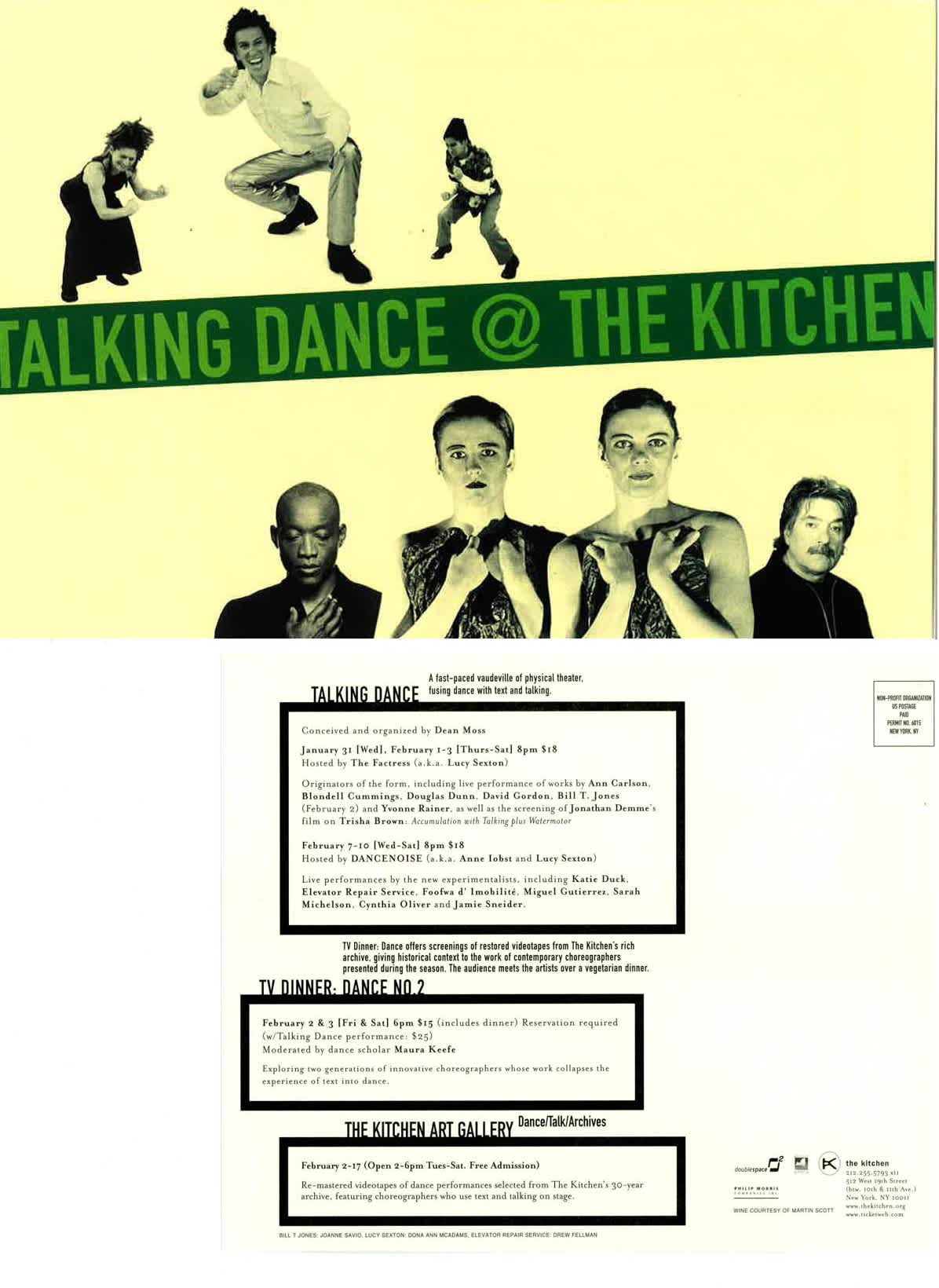

In 1995, the series title Working in the Kitchen was changed to Dance in Progress, and then to Dance and Process in 2005. Though four choreographers now participate rather than eight, and artist-facilitators lead the workshop process rather than The Kitchen’s curators, the structure of the program is more or less the same now as it was in 1990. The group works together for ten weeks, developing a sense of community and trust that echoes the dynamics that marked the early years of dance programming at The Kitchen, when Eric Bogosian worked to establish interpersonal connections through curating Dancing in the Kitchen. The artist-facilitators are usually alums of Dance and Process themselves, and have included Sarah Michelson, Yasuko Yokoshi, and Miguel Gutierrez; the current facilitators are Yve Laris Cohen and Moriah Evans. Since 2005, the program has hosted artists such as Melanie Maar, Antonio Ramos, Kim Brandt, Angie Pittman, mayfield brooks, and Lauren Bakst. Dance and Process is The Kitchen’s longest-running program series, and it builds on the intention of creating opportunities for emerging artists to experiment that defined The Kitchen’s previous dance series.

The types of relationships formed between artists and The Kitchen through dance programming have the potential to impact an artist’s relationship to their own art and practice. The Kitchen’s program formats give choreographers rehearsal and performance space, along with support from staff and peers, with the aim of fostering freedom in creation. Additionally, there are opportunities for artists to return to the space to present work as part of different programs over time. This is a pattern traceable in our institution’s current relationships with artists, just as it was with artists like Jones and Streb when they were creating their first works. For instance, with after summer, Bakst is continuing a line of questioning that she began when she participated in Dance and Process in spring 2018. Each of her works since Dance and Process has built on the discoveries of the previous one as she has developed them in different contexts and forms, such as in artist’s books, at other performance institutions in New York, and now at Queenslab in her residency through The Kitchen.

The existence and nature of Dance and Process today is a continuation of the legacy of experimental dance programming at The Kitchen. Choreographers are still exploring, still working in conversation with one another, and still making work that they continue to develop even after the final performance. Since the beginning, The Kitchen’s dance programming has been designed to allow artists to do this, giving them the freedom to create, succeed, fail, and come back to do it again. Whether artists are Dancing in the Kitchen or “not in the kitchen,” the goal of centering them and their visions is as alive today as it was in 1978.